Money, Funny-Money And Crypto

That the post-industrial era of fiat currencies is coming to an end is becoming a real possibility. Major economies are now stalling while price inflation is just beginning to take off, following the excessive currency debasement in all major jurisdictions since the Lehman crisis and accelerated even further by covid.

The dilemma now faced by central banks is whether to raise interest rates sufficiently to tackle price inflation and lend support to their currencies, or to take one last gamble on yet more stimulus in the hope that recessions can be avoided.

Politics and neo-Keynesian economics strongly favour monetary inflation and continued interest rate suppression. But following that course leads to the destruction of currencies. So, how should ordinary people protect themselves from currency risk?

To assist them, this article draws out the distinctions between money, currency, and bank credit. It examines the claims of cryptocurrencies to be replacement money or currencies, explaining why they will be denied either role. An update is given on the uncanny resemblance between current neo-Keynesian monetary inflation and support for financial asset prices, compared with John Law’s proto-Keynesian policies which destroyed the French economy and currency in 1720.

Assuming we continue to follow Law’s playbook, an understanding why money is only physical gold and silver and nothing else will be vital to surviving what appears to be a looming crisis in financial assets and currencies.

Introduction

With the recent acceleration in the growth of money supply it is readily apparent that government spending is increasingly financed through monetary inflation. Those who hoped it would be a temporary phenomenon are being shown to have been overly optimistic. The excuse that its expansion was only a one-off event limited to supporting businesses and consumers through the covid pandemic is now being extended to seeing them through continuing logistics disruptions along with other unexpected problems. We now face an economic slowdown which will reduce government revenues and, according to policy planners, may require additional monetary stimulation to preclude.

Along with never-ending budget deficits, for the foreseeable future monetary inflation at elevated levels is here to stay. The threat to the future purchasing power of currencies should be obvious, yet few people appear to be attributing rising prices to prior monetary expansion. David Ricardo’s equation of exchange whereby changes in the quantity of money are shown to affect its purchasing power down the line has disappeared from the inflation narrative and is all but forgotten.

That the users of the medium of exchange ultimately determine its utility is ignored. It is now assumed to be the state’s function to decide what acts as money and not its users. Instead, we are told that the state’s fiat currency is money, will always be money and that prices are rising due to failures of the capitalist system. Central to the deception is to call currency money, and to persist in describing its management by the state as monetary policy. And money supply is always the supply of fiat currency in all its forms.

That these so-called monetary policies have failed and continue to do so is becoming more widely appreciated. It is the anti-capitalistic attitude of state planners which absolves them from the blame of mismanaging the relationship between their currencies and economies by blaming private sector actors when their policies fail. Instead of acting as the people’s servants, governments have become their controllers, expecting the public’s sheep-like cooperation in economic and monetary affairs. The state issues its currency backed by unquestioned faith and credit in the government’s monopoly to issue and manage it. Seeming to recognise the potential failure of their currency monopolies many central banks now intend to issue a new version, a central bank digital currency to give greater control over how citizens use and value it.

Without doubt, the dangers from fiat currency instability are increasing. Never has it been more important for ordinary people, its users, to understand what real money constitutes and its difference from state-issued currencies. Not only are new currencies in the form of central bank digital currencies being proposed but some suggest that distributed ledger cryptocurrencies, which are beyond the control of governments, will be adopted when state fiat currencies fail, an eventual development for which increasing numbers of people expect.

The currency scene is descending into a confusion for which policy planners are unprepared. Fiat currencies are failing, evidenced by declining purchasing power. Not only is it the lesson of history; not only are governments resorting to the printing press or its digital equivalent, but it is naïve to think that governments desire monetary stability over satisfying the interests of one group over those of another. By suppressing interest rates, central banks favour borrowers over depositors. By issuing additional currency they transfer wealth from their governments’ electors. The transfer is never equitable either, with early receivers of new currency getting to spend it before prices have adjusted to accommodate the increased quantity in circulation. Those who receive it last find that prices have risen because of currency dilution while their income has been devalued. The beneficiaries are those close to government and the banks who expand credit by ledger entry. The losers are the poor and pensioners — the people who in democratic theory are more morally entitled to protection from currency debasement than anyone else.

The true role of money

In the late eighteenth century, a French businessman and economist, Jean-Baptiste Say, noticed that when France’s currencies failed during the Revolution, people simply exchanged goods for other goods. A cobbler would exchange the shoes and boots he made for the food and other items he required to feed and sustain his family. The principles behind the division of labour had continued without money. But it became clear to Say that the role of money was to facilitate this exchange more efficiently than could be achieved in its absence. For Keynesian economists, this is the inconvenient truth of Say’s law.

The division of labour, which permits individuals to deploy their personal skills to the greatest benefit for themselves and therefore for others, remains central to the commercial actions of all humanity. It is the mainspring of progress. A medium of exchange commonly accepted by society not only facilitates the efficient exchange of goods produced through individual skills but it allows a producer to retain money temporarily for future consumption. This can be because he has a surplus for his immediate requirements, or he decides to invest it in improving his product, increasing his output, or for other purposes than immediate consumption.

Whether it is a corporation, manager, employee, or sole trader; whether the product be a good or a service— all qualify as producers. Everyone earning a living or striving to make a profit is a producer.

Over the many millennia that have elapsed since the end of barter, people dividing their labour settled on metallic money as the mediums of exchange; recognisable, divisible, commonly accepted, and being scarce also valuable. And as civilisation progressed gold, silver, and copper were coined into recognisable units. These media of exchange in their unadulterated form were money, and even though they were stamped with images of kings and emperors, they were no one’s liability.

Nowadays, humans across the planet still recognise physical gold and silver as true money. But it is a mistake to think they guarantee price stability — only that they are more stable than other media of exchange, which is why they have always survived and re-emerged after alternatives have failed. This is the key to understanding why they guaranteed money substitutes, notably through industrial revolutions, and remain money to this day.

Britain led the way in replacing silver as its long-standing monetary standard with gold, relegating silver to a secondary coinage. In 1817 the new gold sovereign was introduced at the exchange rate equivalent of 113 grains (0.2354 ounces troy) to the pound currency. A working gold standard, whereby bank notes were exchangeable for gold coin commenced in 1821, remaining at that fixed rate until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

By 1900, the gold standard had international as well as domestic aspects. It implied that nations settled balance of payment differences with each other in gold, although in practice this seems to have happened relatively little.

Many smaller nations, while having domestic gold circulation, did not bother to keep physical gold in reserve, but held sterling balances which, again, were regarded as being as good as gold. The Bank of England had a remarkably small reserve of under 200 tonnes in 1900, compared with the Bank of France which held 544 tonnes, the Imperial Bank of Russia with 661 tonnes, and the US Treasury with 602 tonnes. But even though remarkably little gold was held by the Bank of England, over 1,400 tonnes of sovereign coins had been minted in Australia and the UK and were in public circulation. Therefore, some £200m of the UK and its empire’s money supply was in physical gold (the equivalent of £62bn at today’s prices).[i]

The relationship between gold and prices

Metallic money’s purchasing power fluctuates, influenced by long-term factors such as changes in mine output and population growth. Gold is also held for non-monetary purposes such as jewellery though the distinction between bullion held as money and jewellery can be fuzzy. A minor use is industrial. The degree of coin circulation relative to the quantity of substitutes also affects its purchasing power, as experience from nineteenth century Britain attests.

The economic progress of the industrial revolution increased the volume of goods relative to the quantity of money and money-substitutes (bank notes and bank deposits subject to cheques), so the general level of producer prices declined, even though they varied with changes in the level of bank credit. That generally held until the late-1880s, when bank credit in the economy expanded on the back of increased shipments of gold from South Africa. Furthermore, a combination of rising demand for industrial commodities through economic expansion of the entire British empire and more currencies linking themselves to gold indirectly via managed exchange rates against pounds and other gold-backed currencies all contributed to reverse the declining trend of wholesale prices between 1894—1914.

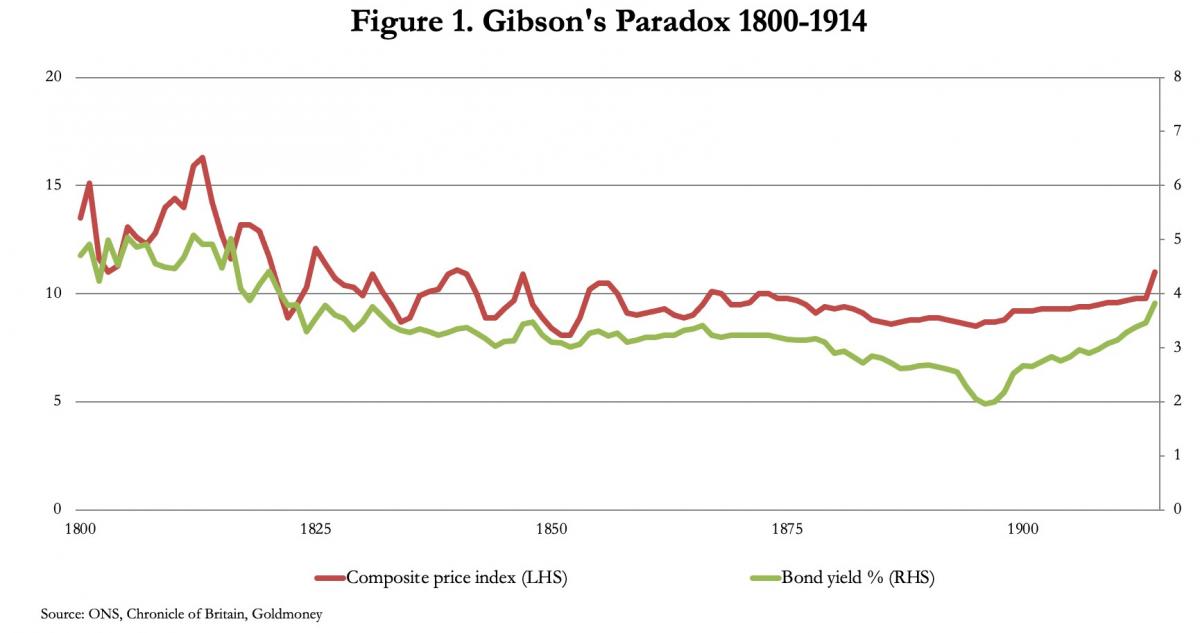

Consequently, wholesale prices no longer declined but tended to increase modestly. This is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 also explodes the myth in central bank monetary policy circles that varying interest rates controls money’s purchasing power by “pricing” money.

Demand for credit is set by the economic calculations of businessmen and entrepreneurs, not idle rentiers as assumed by Keynes who named this paradox after Arthur Gibson, who pointed it out in 1923. The explanation eluded Keynes and his followers but is simple. In assessing the profitability of production, the most important variable (assuming that the means of production are readily available) is anticipated prices for finished products. Changes in borrowing rates, reflecting the affordability of interest that could be paid therefore do not precede changes in prices but follow changes in prices for this reason.[ii]

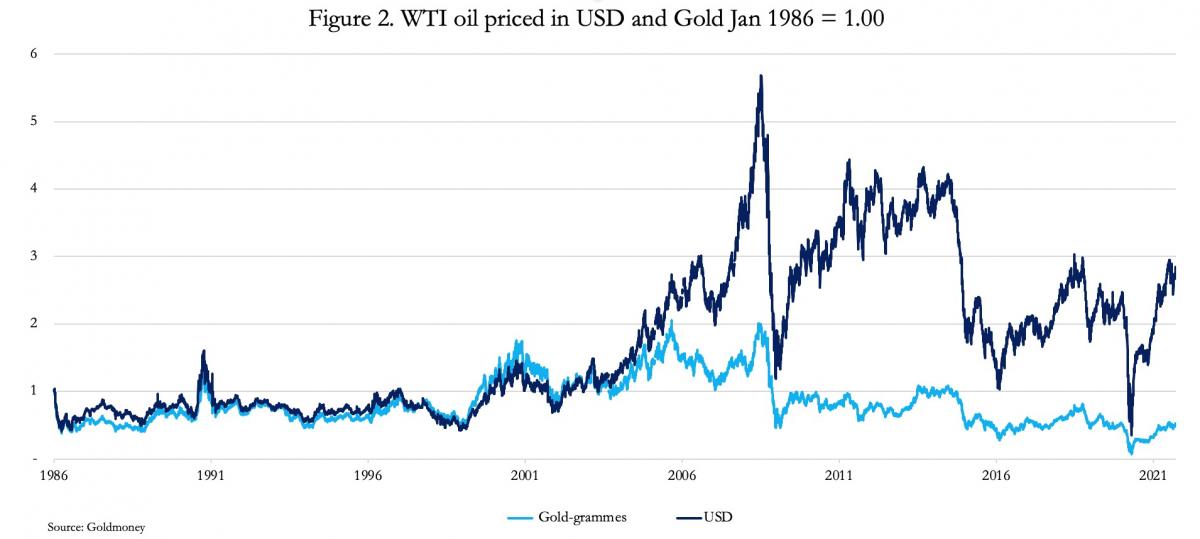

While fluctuations in the sum of the quantities of money, currency and credit affect the general level of prices, there is an additional effect of the value placed on these components by its users. History has demonstrated that the most stable value is placed on gold coin, which is what qualifies it as money. It has been said that priced in gold a Roman toga 2,000 years ago cost the same as a lounge suit today. But we don’t need to go back that far for our evidence. Figure 2 shows WTI oil priced in dollars, the world’s reserve currency, and gold both indexed to 1986. Clearly, the dollar is significantly less reliable than gold as a stable medium of exchange.

So long as gold is freely exchangeable for currency, this stability is imparted to currency as well. When it is suspected that this exchangeability is likely to be compromised, coin becomes hoarded and disappears from circulation. The purchasing power of the currency then becomes dependent on a combination of changes in its quantity and changes in faith in the issuer. Bank deposits face the additional risk of faith in the bank’s ability to pay its debts.

In summary, the general level of prices tends to fall gradually over time in an economy where gold coin circulates as the underlying medium of exchange, and when faith in the currency as its circulating alternative is unquestioned. The existence of a coin exchange facility lifts the purchasing power of the currency above where it would otherwise be without a functioning standard. Even when gold exchange for a fiat currency becomes restricted, the purchasing power of the currency continues to enjoy some support, as we saw during the Bretton Woods Agreement.

The distinction between money and currency

So far, we have defined money, which is metallic and physical. Now we turn to what is erroneously taken to be money, which is currency. Originally, the dollar and pound sterling were freely exchangeable by its users for silver and then gold coin, so state-issued currencies came to be assumed to be as good as money. But its exchangeability diminished over time. In the United Kingdom exchangeability of sterling currency for gold coin ceased with the outbreak of hostilities in 1914, though sovereigns still exist as money officially today. They are simply subject to Gresham’s law, driven out of general circulation by inferior currency. The post-war gold standard of 1925-32 was a bullion standard whereby only 400-ounce bars could be demanded for circulating currency, which failed to tie in sterling to money proper.

In the United States, gold coin was exchangeable for dollars in the decades before April 1933 at $20.67 to the ounce. Bank failures following the Wall Street crash encouraged citizens to exchange dollar deposits for gold, and foreign holders of dollar deposits similarly demanded gold, leading to a drain on American gold reserves. By Executive Order 6102 in April 1933 President Roosevelt banned private sector ownership of gold coin, gold bullion and gold certificates, thereby ending the gold coin standard and forcing Americans to accept inconvertible dollar currency as the circulating medium of exchange. This was followed by a devaluation of the dollar on the international exchanges to $35 to the ounce in January 1934.

The entire removal of money from the global currency system was a gradual process, driven by a progression of currency events, until August 1971 when President Nixon ended the Bretton Woods Agreement. From then on, the US dollar became the world’s reserve currency, commonly used for pricing commodities and energy on international markets. But following the Nixon shock, the dollar had become purely fiat.

Unlike gold coin, which has no counterparty risk, fiat currency is evidence of either a liability of an issuing central bank or of a commercial bank. It is not money. The fact that money, being gold or silver coin does not commonly circulate as media of exchange, cannot alter this fact. Since the dawn of modern banking with London’s goldsmiths in the seventeenth century, who deployed ledger debits and credits, most currency entitlements have been held in bank deposits, which are not the property of deposit customers, being liabilities of the banks and owed to them. It started with depositors placing specie with goldsmiths or transferring currency to them from other accounts on the understanding a goldsmith would deploy the funds so acquired to obtain sufficient profit to pay a 6% interest on deposits. To earn this return, it was agreed by the depositor that the funds would become the goldsmith’s property to be used as the goldsmith saw fit.

Goldsmiths and their banking successors were and still are dealers in credit. As the goldsmiths’ banking business evolved, they would create deposits by extending credit to borrowers. A loan to the borrower appeared as an asset on a goldsmith’s balance sheet, which through double-entry book-keeping was balanced by a liability being the deposit facility from which the borrower would draw down the loan. Thus, money and currency issued by banks as claims upon them were replaced entirely by book-entry liabilities owed to depositors, encashable into specie, central bank currency or banker’s cheque only on demand.

Through the expansion of bank credit, which is matched by the creation of deposits through double-entry book-keeping, commercial banks create liabilities subject to withdrawal as currency to this day. That there is an underlying cycle of expansion and contraction of bank credit is evidenced by the composite price index and bond yields between 1817 and 1885 shown in Figure 1 above. But so long as money, that is gold coin, remained exchangeable with currency and bank deposits on demand, fluctuations in outstanding bank credit only had a relatively short-term effect on the general level of prices. And as explained above, the expansion of the quantity of above-ground gold stocks from South African mines in the late 1880s contributed to the general level of prices increasing in the final decade of the nineteenth century until the First World War.

Following the Great War, the earlier creation of the Federal Reserve Board in the United States led to the expansion of circulating dollar currency, fuelling the Roaring Twenties and the Wall Street bubble, followed by the Wall Street crash and the depression. These calamities were the inevitable consequence of excessive credit creation in the 1920s. The error made by statist economists at the time (and ever since) was to ignore what caused the depression, believing it to be a contemporaneous failure of capitalism instead of the consequence of earlier currency debasement and interest rate suppression. From then on, this error has been perpetuated by statists frustrated by the discipline imposed upon them by monetary gold. The solution was seen to be to remove money from the currency system so that the state would have unlimited flexibility to manage economic outcomes.

With America dominating the global economy after the First World War, her use of the dollar both domestically and internationally had begun to dominate global economic outcomes. The errors of earlier currency expansion ahead of and during the Roaring Twenties, admittedly exacerbated by the introduction of farm machinery, led to a global slump in agricultural prices the following decade. And the additional error of Glass Stegall tariffs collapsed global trade in all goods.

Following the Second World War, secondary wars in Korea and Vietnam led to exported dollars being accumulated and then sold by foreign central banks for American’s gold reserves. In 1948, America had 21,628.4 tonnes of gold reserves, 72% of the world total. By 1971, when the facility for central banks to encash dollars for gold was suspended, US gold reserves had fallen to 12,398 tonnes, 34% of world gold reserves. Today it stands officially at 8,133.5 tonnes, being less than 23% of world gold reserves — figures independently unaudited and suspected by many observers to overstate the true position.[iii]

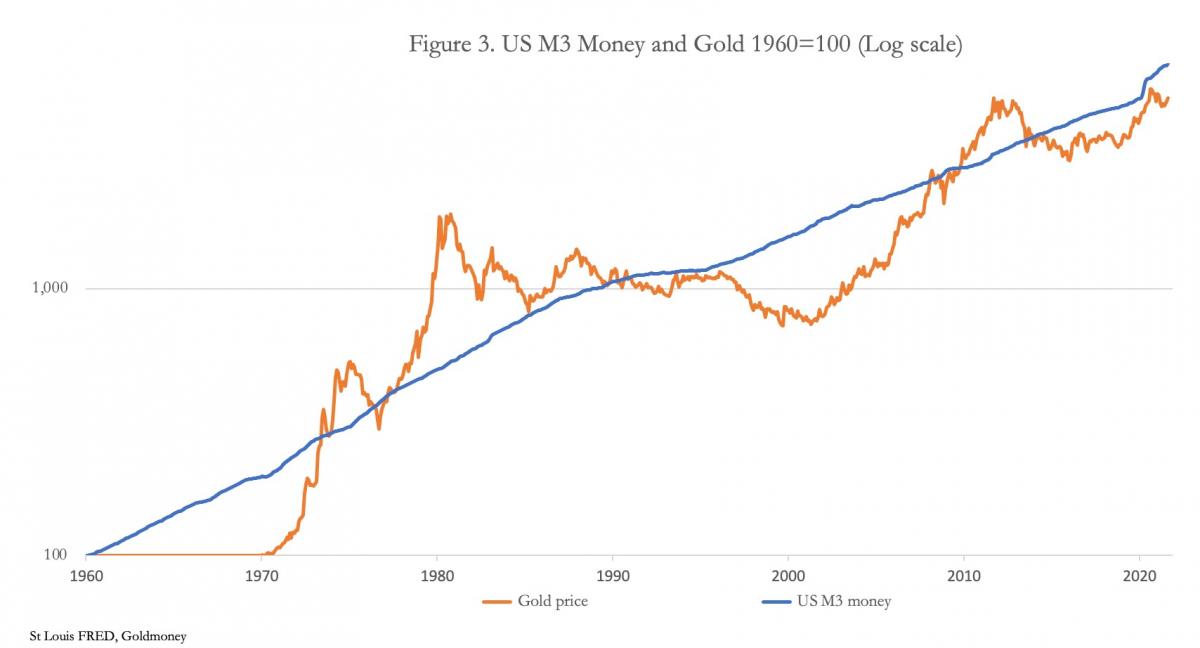

The consequences of currency expansion for the relationship between money and currency since the two were completely severed in 1971 is shown in Figure 3.

Since 1960 (the indexed base of the chart) above-ground gold stocks have increased from 62,475 tonnes by about 200% to 189,000 tonnes — offset to a large degree by world population growth.[iv] M3 broad money has increased by 70 times, the disparity in these rates of increase being adjusted by the increase in the dollar price of money, with the dollar losing 98% of its purchasing power relative to gold. By basing the chart on 1960 much of the currency expansion which led to the collapse of the London gold pool in the mid-1960s is captured, illustrating the strains in the relationship that led to the Nixon shock.

he rival status of cryptocurrencies

Over the last decade, led by bitcoin cryptocurrencies have become a popular hedge against fiat currency debasement. Bitcoin has a finite limit of 21 million coins, having less than 2¼ million yet to be mined. And of those issued, some are irretrievably lost, theoretically adding to their value.

Fans of cryptocurrencies are unusual, because they have grasped the essential weakness of state-issued fiat currencies ahead of the wider public. Armed with this knowledge they claim that distributed ledger technology independent from governments will form the basis of tomorrow’s money. It has led to a speculative frenzy, driving bitcoin’s price from a reported 10,000 for two pizzas in 2010 (therefore worth less than a cent each) to over $60,000 today. If, as hodlers hope, bitcoin replaces all state-issued fiat currencies when they fail, then the increase in its dollar value has much further to go.

In theory there are reasons that bitcoin and similar cryptocurrencies can become media of exchange in a limited capacity, but never money, the basis that all currencies referred to for their original validity. Indeed, some transactions following the original pizza purchase have occurred since, but they are very few.

The reasons bitcoin or rival cryptocurrencies are unlikely to be accepted widely as currencies, let alone as a replacement for money, are best summed up in the following bullet points.

To replace money, as opposed to currencies, bitcoin would have to be accepted as a replacement for both gold and silver. Beyond the imagination of tech-savvy enthusiasts, making up perhaps less than one in two hundred transacting humans,[v] it is impossible to see bitcoin achieving this goal, because they represent a vanishingly small number of the global population. There can be little doubt that if fiat currencies lose their utility the overwhelming majority of transacting individuals will desire physical money, and not another form of digital media, which currencies in the main and cryptocurrencies have become.

- Despite the advance of technology not everyone yet possesses the knowledge, media, or the reliable electricity and internet connections to conduct transactions in cryptocurrencies. Remote theft of them is easier and more profitable than that of gold and silver coin. Cryptocurrencies are too dependent on undefinable risk factors for transactional ubiquity.

- The number of rival cryptocurrencies has proliferated. It is estimated that there are now over 6,800 in existence compared with 180 government-issued currencies. They represent both an inflation of numbers and values, which if unsatisfied already makes the seventeenth century tulip mania look like to have been a relatively minor speed bump in comparison. In only a decade they have grown to $750 billion in value based on an unproven concept stimulating unallayed human greed at the expense of considered reason.

- By way of contrast, gold’s strength as money is its flexibility of supply from other uses combined with its record of ensuring price stability. As we saw in Figure 1’s illustration of the relationship between prices and borrowing costs, assuming the factors of production are available the stability of prices under a gold standard permits an assessment of final product values at the commencement of an investment in production. There is no such certainty with bitcoin or rival cryptocurrencies because a strictly finite quantity would make it impossible to calculate final prices at the end of an investment in production. Without providing the means for economic calculation, any money or currency replacement will fail.

- Unless they disappear with their currencies, central banks will never sanction distributed ledger currencies beyond their control acting as a general medium of exchange. This is one reason why they are working to introduce their own central bank digital currencies, allowing them to maintain statist control over currencies while extending powers over how they are used. Furthermore, central banks do not own cryptocurrencies, but they do officially own 35,554 tonnes of gold, having never discarded true money completely.[vi] Events have proved that they are even reluctant to allow monetary gold to circulate, not least because it would call into question the credibility of their fiat currencies. But if there is a fall-back position in the demise of fiat, it will be based on central bank gold and never on a private-sector cryptocurrency.

We should also consider what happens to cryptocurrencies in the event of a fiat currency collapse. The point behind any money or currency is that it must possess all the objective value in a transaction with all subjectivity to be found in the goods or services being exchanged. It requires the currency to be scarce, but not so much that its value measured in goods is expected to continually rise. If that was the case, then its ability to circulate would become impaired through hoarding.

We are left with questioning whether bitcoin can ever possess a purely objective value in transactions. Their potential role as a transacting currency will also evaporate along with fiat because these will be the circumstances where all currencies which cannot be issued as credible gold substitutes will become valueless, because if any currency is to survive the end of the fiat regime it will require action by central banks combined with new laws and regulations which can only come from governments. The nightmare for crypto enthusiasts is that central banks will be forced eventually to mobilise their gold reserves to back credibly what is left of their currencies’ collapsing purchasing power.

We are providing an answer to another question over the fate of cryptocurrencies in the event that central banks are forced to mobilise their gold reserves, turning fiat currencies into credible money substitutes. Admittedly, it is unlikely to be a simple decision with the problem beyond the understanding of statist policy advisers and with competing interests seeking to influence the outcome. But, there can be only one action that will allow the state and banking system to retain control over currencies and credit, which is to back them with gold reserves, preferably with a gold coin standard.

When that moment is anticipated, cryptocurrencies as potential circulating currencies will become fully redundant. They are then likely to lose most of or all their value as replacement currencies. Furthermore, it is hard to find anyone who currently holds a cryptocurrency who does not hope to cash in by selling them at higher prices for their national currencies. They have been bought for speculation and investment with little or no intention of ultimately spending them. Therefore, we can assume that the demise of fiat currencies, far from inviting replacements by bitcoin and its imitators, will also mean the death of the cryptocurrency phenomenon in a general return towards a money standard, which always has been physical and metallic.

The progression towards currency destruction

In last week’s article for Goldmoney I suggested four waypoints to mark the route towards the ending of the fiat currency system. The similarity of current events with those of John Law’s inflation and subsequent collapse of the Mississippi bubble and of the French livre so far is striking, but this time it’s on a global scale. The John Law experience offers us a template for what is already happening to financial assets and currencies today — hence the four waypoints[vii].

Briefly described, John Law was a proto-Keynesian money crank who operated a policy of inflating the values of his principal assets, the Banque Royale and his Mississippi venture, by issuing shares in partly paid form with calls due later. Ten per cent down translated into fortunes for early subscribers as share prices rose from L140 in June 1717 to over L10,000 in January 1720, fuelled by a bitcoin-style buying frenzy. But when calls became due in January 1720 and a scheme to merge the Banque Royale with the Mississippi venture was proposed, shares began to be sold to pay the calls and take up rights to new issues. Law used his position as controller of the currency to issue fiat livres to buy shares in the market to support prices, measures that finally failed in May. Priced in livres, the shares fell to under 3,500 by November. In sterling, they fell from £330 in January to below £50 in September. After October, there was no exchange rate for livres against sterling implying the livre had lost all its exchange value.[viii]

By injecting cash into investing institutions in return for government bonds, central banks are following a remarkably similar policy today. Quantitative easing by the US’s central bank, which since March 2020 has injected over $2 trillion into US pension funds and insurance companies to invest in higher risk assets than government and agency bonds, is no less than a repetition of John Law’s policy of inflating asset values to ensure a spreading wealth effect, while ensuring finance is facilitated for the state.

Last night (3 November) the Fed was forced to announce a phased reduction of quantitative easing to allay fears of intractable price inflation. The question now arises as to how many months of QE reduction it will take to deflate the financial asset bubble. And what will then be the Fed’s response: will QE be increased again in a repetition of the John Law proto-Keynesian mistakes?

There comes a point where the prices of goods reflect the increased quantity of currency in circulation. Increases in the general level of prices inevitably lead to rising levels for interest rates, and the creation of credit in the main banking centres begin to go into reverse. John Law found that share prices could then no longer be supported, and the Mississippi bubble burst in May 1720; a fate which equity markets today will almost certainly face, because price rises for goods and services are now proving intractable.

The outcome of Law’s proto-Keynesianism was a collapse in Mississippi shares, and the complete destruction of the livre. The similarity with the situation in financial markets today is truly remarkable. There are now no good options for policy makers. Hampered by similar neo-Keynesian errors and beliefs, central bankers and politicians lack the resolve to stop events leading inexorably towards the destruction of their currencies. The first waypoint in last week’s article for Goldmoney is now being seen: a growing realisation that major economies, particularly the US and UK, face the prospect of a combination of rising prices accompanied by an economic slump, frequently diagnosed as stagflation.

Stagflation is a misnomer. Monetary inflation is a con which in smaller doses provides the illusion of stimulus. But there comes a point where the transfer of wealth from the productive economy to the government is too great to bear and the economy begins to collapse. While it is impossible to judge where that point lies, the accumulation of monetary inflation in recent years now weighs heavily on all major economies.

The conditions today closely replicate those in France in late-1719 and early 1720. Prices were rising in the rural areas as well as in the cities, impoverishing the peasantry and asset inflation was running into headwinds, about to impoverish the beneficiaries of the bubble’s wealth effect as well.

Conclusion

If central banks decide to protect their currencies, they must let markets determine interest rates. With prices rising officially at over 5% in the US (more like 15% on independent estimates) the rise in interest rates will not only crash all financial asset values from fixed interest to equities, but force governments to rein in their spending to eliminate deficits. This will involve greater cuts than currently indicated, because of loss of tax revenues. Indeed, mandatory spending will put socialising governments in an impossible position.

But even these measures are unlikely to protect currencies, because of extensive foreign ownership of the US dollar. Foreigners hold total some $33 trillion in financial assets and bank deposits, much of which will be liquidated or lost in a bear market. Long experience suggests that funds rescued from overexposure to foreign currencies will be repatriated.

Alternatively, attempts to continue the inflationary policies of Keynesian money cranks will undermine currencies more rapidly, but this is almost certainly the line of least policy resistance — until it is too late.

It has never been more important for the hapless citizen to recognise what is happening to currencies and to understand the fallacies behind cryptocurrencies. They are not practical replacements for state-issued currencies and are likely to turn out to be just another aspect of the financial bubble. The only protection from an increasingly likely collapse of the fiat money system and all that sails with it is to understand what constitutes money as opposed to currency; and that is only physical gold and silver coins and bars.

________________________________

[i] Quoted in Central Bank Gold reserves, an historical perspective since 1845 by Timothy Green (published by the World Gold Council, November 1999)

[ii] The confusion over the relationship between interest rates and prices is reflected in Gibson’s paradox, which defied explanation by Keynes and other statist economists. A fuller explanation of the phenomenon is found at https://www.goldmoney.com/research/goldmoney-insights/gibson-s-paradox

[iii] Goldmoney estimate in 2012 and extrapolation of mone production since. See https://www.goldmoney.com/images/media/Files/Old_GM_WP/theabovegroundgoldstock.pdf

[iv] Generously assuming that there are as many as 35,000,000 souls globally willing to use cryptocurrencies for daily transactions. Admittedly, they may be pockets of them in places like California, but if its lack of supply means that their value rises, they will be hoarded and not spent.

[v] Caution should be exercised over the actual figure, derived from IMF statistics, because the IMF allows swapped and leased gold to be included in them, leading to an unknown degree of double counting.

[vi] See https://www.goldmoney.com/research/goldmoney-insights/waypoints-on-the-road-to-currency-destruction-and-how-to-avoid-it

[vii] See Antoine E Murphy’s Richard Cantillon — Entrepreneur and Economist (Oxford University Press) for a financial account of Law’s Mississippi bubble and its bursting.

[viii] World Gold Council figures.

*********